I Belonged in Louisiana

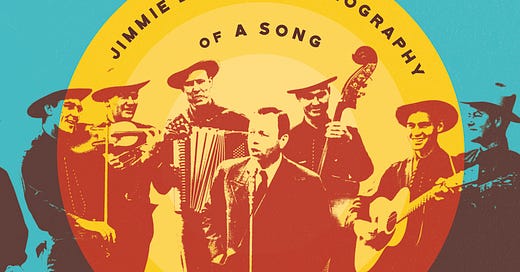

An extended excerpt from my new book, You Are My Sunshine: Jimmie Davis & the Biography of a Song

Today, I’m sharing an extended excerpt from my new book, You Are My Sunshine: Jimmie Davis & the Biography of a Song. LSU Press published it on Wednesday.

I’ve enjoyed speaking about it in New Orleans, Alexandria, and Baton Rouge. Next week, I’ll be in Hammond, New Orleans, and Baton Rouge, and the following week, in Baton Rouge and Shreveport.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Something Like the Truth: By Robert Mann to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.